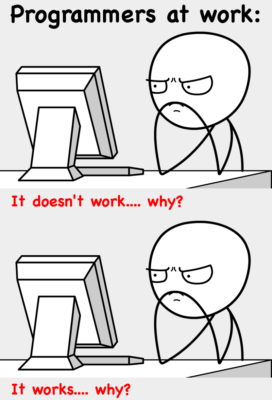

You read through the code. You read it again to make sure you understand what it’s doing. Your left eye starts twitching. You read the code a third time.

“WTF was wrong with the person who wrote this?”

I hate how often I react this way. It’s a quick default that’s hard to reset — immediate annoyance as if the developer or engineer responsible for writing whatever I’ve come across was scattering landmines. It’s easy to shit on the people who came before you. They’re usually not around to defend themselves or provide context. It’s much harder to calm down, and think things through. An initial reaction of “WTF?!” is entirely valid (You’re gonna feel what you’re gonna feel.), but getting stuck on the frustration and not going further is unfair to your predecessors and causes you to miss out on learning.

“How” a problem was solved/band-aided/kicked-down-the-road is usually the root of those frustrations, but the next step is thinking through the “Why” of the solution, which is often the source of useful information.

The code might be stupid, but there’s usually a reason. Maybe:

- Something stupid upstream brought its stupid with it. Alternatively, something stupid downstream needed more stupid.

- The dev/engineer was told to do it that way.

- The dev/engineer was getting pulled in 1000 different directions and needed to make a fast band-aid.

- The dev/engineer was doing the best they knew how.

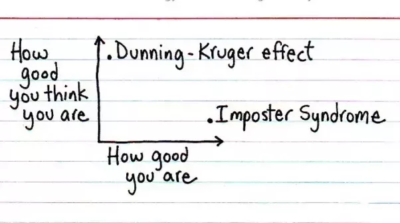

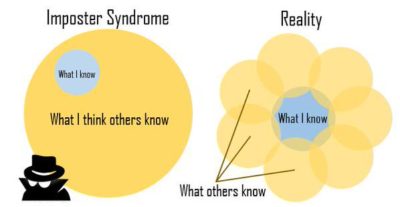

- It’s actually not stupid. You just think you know more than you do.

That doesn’t rule out laziness or malice, but they’re much rarer and shouldn’t be the default assumption. When we run across goofy looking code and configs, we need to respect the constraints and context the person who wrote them faced. Note: That the person might actually be an idiot is a real, intractable constraint. How would you have fixed that?

Thinking through and learning the “whys” that caused the stupid will help you understand the context of the problem you’re currently facing. You’ll learn about not only technical pitfalls, but cultural ones as well. A lot of the stupid that shows up in code has nothing to do with the technical competence of the person who wrote it and everything to do with their manager or the company at large.

How many times has the past version of you done something stupid that harmed future you? How many times have you looked at something you made a year ago and thought “What was I thinking?” Like any skill, if you’re not embarrassed by some of the code and configs you’ve written in the past you’re 1.) an egotistical monster, and 2.) not getting better. Knowing that, allow some grace for yourself and the people who came before you.

I can’t say I’ve mastered this skill yet. Sometimes, in moments of frustration, I flat out suck at it. But I’m trying and that’s kind of the crux to all this. Everyone is trying, no one has arrived, and the more we empathize with the unknown constraints of those who came before us, the better off we’ll be.

Adapted from original link